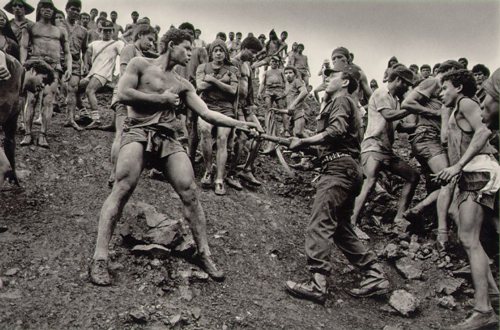

This photograph was taken by Sebastiao Salgado at a gold mine in Brazil. I first saw it in a room at the University I attend. As an idealistic and aspiring academic I felt moved by the raw power of the worker as he resisted the guard. Ever since then I have had a copy of this picture in my study areas. It reminds me that my life is not just about doing good, but that I have a moral duty to alleviate as much suffering in this world as I can. It reminds me that sometimes I need to resist those in power to protect the weak. I believe that is part of the heritage that Christ has given us.

Egon Friedell

In this regard I was recently provoked to thought by something Egon Friedell has said about the Christian tradition. I had never heard of Egon Friedell, until reading a book by Clive James entitled ‘Cultural Amnesia’ (which I whole-heartedly recommend), but I think I really like him. James describes him as the ‘polymath’s polymath’. Yet, Friedell was not merely a book-worm but was also one of the most famous cabaret artist’s of his day in a city (Vienna) full of performers. Before discussing his ideas I wanted to share one tid-bit from his life which was (oddly) inspiring for me:

‘On the day of the AnschluB in 1938, Friedell saw the storm troopers marching down the street, on their way to the building in which he had his apartment full of books. He was only a few floors up but it was high enough to do the job. On his way out of the window he called a warning, in case his falling body hit an innocent passer-by.’

His magnum opus ‘Cultural History of the Modern Age’ contains this line: ‘Mankind in the Christian Era possesses one huge advantage over the ancients: a bad conscience’. Now it seems that neither James nor Friedell were Christians but they recognised something that the world had been given because of Christianity. In James’ words, ‘When Friedell talked about a bad conscience, he meant the mind that was capable of seeing that might and right were not the same thing’.

One challenge with making this distinction is discerning it amidst the normalising power of culture. Seeing oppression and pain inflicted by those in power is difficult when those causing such situations are the same people we revere or respect; it is harder still is to resist it. ‘Most men’ James notes ‘bend with the breeze: which is to say, they go with the prevailing power. But a few do not. With or without Christ’s help, they grow a bad conscience. Thank God for that.’

Yet, what haunts me more is that, in the words Albert Camus, ‘I [find] that there [are] sweet dreams of oppression within me’. I really believe that ‘it is the nature and disposition of almost all men… to exercise unrighteous dominion’ (D&C 121:39); and this includes me. Friedell’s ‘bad conscience’ must work inward as much as it flows outward; I must check myself against the tendencies that I have to use any ‘perceived’ authority I might have to justify my own prejudices. James’ oppressive breeze blows both from within and from without.

The last century saw many idealistic and bright people bend with that breeze, and yet, within the Christian heritage is the ‘bad conscience’, which urges us to resist oppressive behaviour, even from ourselves. I wonder whether I have been true to my tradition. I wonder whether I have stood up for the down-trodden and the out-cast. I wonder whether my respect for authority has led me to turn a blind-eye to unrighteous dominion (wherever that is found). I hope I can be rigid in one of the few senses I see as important; that I will never concede to view that power leads inevitably to truth.

Comments 28

Rico,

brilliant! Thank you for the photograph. We as LDS, of all people, should be haunted by so many things that we accept as we goose-step to supposed authority. It is all around us from issues of immigration, health care, and most importantly, IMO, issues of Christian crusades and torture in the name of Christian “duty.”

http://themormonworker.wordpress.com/2008/12/13/in-defense-of-blackwater-gangs-neocons/

and on the other hand your religion believes the wars that are happening now are necessary to bring about the end of the world scenario and all that, right? Hence the sit back and watch it happen approach… Kind of like God too actually, huh?

#2 – Nope.

Christianity did not give the world a conscience. Christianity is not needed to discern right from wrong. Rico, I would love to hear some foundation for this assumption made by James and/or Friedell and endorsed by you in this post.

Thanks Rico!!

Personally, I think it is important to recognize that this idea has a downside. And, if, as Dexter says, Christianity is not what gave the world a conscience, then we ought to blame the atheists, buddhists, muslims, etc. etc. as well. The truth is, when we feel a moral duty to alleviate as much suffering as we can, this can quickly blow up into ideals that become un-Christlike. I believe we are seeing this the world over right now.

I don’t want to be political, but at some level, in most developed countries, I am forced to pay for the healthcare of my neighbor. I am forced to pay into a system that will sustain retired people now, but will not support me when I retire. Everywhere I turn people are forcing me to be altruistic (an very un-altruistic action), in the name of altruism!! As Dexter points out, it ain’t just Christians responsible for this type of nonsense.

I think it’s important to understand that altruism has a downside as well that can stifle innovation, hamper personal growth, and creates a society that will ultimately fail if it becomes something that is obligatory. I believe it is noble to alleviate suffering. But I also recognize suffering is a part of life, and that some will suffer while others prosper. I wouldn’t have it any other way! It is also noble to take pride in one’s accomplishments, earn money, provide for oneself, and take control of one’s destiny.

#2 – I am not sure that I agree with that, sorry. Wars may happen, i think my job is try and alleviate what suffering I can. Although I am not an expert on these things, I think that the Church and God try to do the same.

#4 – I think you may have mis-understood my post, or not read it very closely. Firstly, James and Friedell are/were atheists, so I am farily confident they would never have argued that Christianity gave the world a conscience. I do not believe that either. It seems that Friedell’s point (and it is his point, which both I and James have picked up on) is that Christianity has the potential within it and has built into its tradition this ‘bad conscience’ which assumes that the distinction between might and right was not so easily made prior to the Christian era. I am not a historian, as Friedell was, and I can acknowledge that his study may have had a eurocentric bias, but I think that his major point is essentially right. Moreover, James modifies this to add an ‘ought’ to possess a bad conscience which I agree with and is why I wrote this post. I do not see Christians, including myself, fulfill this very well. Nor am I arguing that religious people inevitably possess this while non-religious people do not. I am saying that this should be part of our religious tradition. James believed that the Christian conscience preceded the all-important liberal conscience. He sees the ‘bad conscience’ as an essential feature of both. And as I put in the post people can develop this bad conscience with or without Christ.

#5 – I guess your right that it may seem silly to force someone to altruism, and yet I feel happy with the welfare system we have in the UK. I am happy to be taxed so that others can be helped. But you right this is another issue. I guess, in a similar vein, I believe that sometimes people will take advantage of another individual’s good nature but that is ok because I feel that I am to help all people not just those I think deserve it or who will really benefit from it.

Rico,

I suspect from the comments thus far that your readers do not have enough background in ethics / theology / history to understand many of the implications of your post or the nature and meaning of the distinction between conscience, bad conscience, and the striving for a good conscience. #5’s reading is so weak I’m not sure its worth the effort to correct it, or even just mock it.

Regardless, not having read Friedell perhaps you can describe how he makes the distinction between the Hebrew and Christian ethical traditions regarding a bad conscience. It seems to me that the weight of Hebrew teachings of our responsibility for the other could be seen as equally productive of a bad conscience. Although Christianity does have a very powerful tool of bad conscience in Christ’s sacrifice.

I think your last paragraph is significant in the American Mormon context for two reasons.

First, the American narrative, broadly speaking, is one in which we are always already on the right track, the expression of our military, political and economic power is always put into heroic narratives that contain a number of self serving expressions: The gratitude for military actions and sacrifice of service members for “protecting our freedoms” regardless of the actual purpose or consequence of our military action. The expression that our exercise of power is itself an outgrowth of our innate goodness, and conversely that opposition to our program is a sign of either innate evil on the part of our “enemies” or lack of moral clarity on the part of our allies. There is also the implicit idea that there is no “problem” that our might and our innate goodness lack the power to solve.

Second, this matters in the Mormon context because of the way the ideology of nationalism and militarism, and their self justifying narratives, have been broadly woven into the interpretation of Mormon texts and into Mormon theology. This has a particularly toxic effect when combined with a certain view of agency within the church and of the individual’s relation to the power of governments. The result at times is the whole sale insistence on passivity in any context, even those that should invoke our ethical outrage and a call to action. I think one of the problems with a lot of Mormon ideology (as opposed to theology or doctrine) is that it is so heavily influenced by a tribalism that defines the other as always a threat to the self. The idea of the bad conscience is a good tool for dealing with that problem but one has to be willing to go through the cognitive dissonance of a bad conscience in order for it to work. A lot of people in many branches of American Christianity including Mormonism use their religion as a means of avoiding just such cognitive dissonance or bad conscience. Christianity, in that context is about creating ideological certainty regarding the correctness of one’s beliefs, relation to power, and one’s individual salvation. Within the Mormon context your statement that power never leads inevitably to truth, is radical in its ethical potential, but also directly counter to an ideology that many Mormon’s believe to be a theology. So that is an interesting place to be.

Rico, while I don’t know anything about Friedell, you quote him as saying that ‘Mankind in the Christian Era possesses one huge advantage over the ancients: a bad conscience’, which could be causation or could be correlation. Christianity could have caused the world to grow a bad conscience or people could have simply developed a bad conscience during the same era. But you clearly think it was causation. You say, “Now it seems that neither James nor Friedell were Christians but they recognised something that the world had been given BECAUSE of Christianity.” You say the world was given a conscience BECAUSE of Christianity but then you say in comment 6 that you do not believe that. So I don’t see how you can accuse me of not reading your post carefully or not understanding it when I stated that you focused on Christianity causing the bad conscience. Perhaps it wasn’t written very carefully? (this is not meant to be snarky at all, I am just saying I don’t think I misinterpreted it or didn’t read it closesly enough).

You also said: “The last century saw many idealistic and bright people bend with that breeze, and yet, within the Christian heritage is the ‘bad conscience’, which urges us to resist oppressive behaviour, even from ourselves.”

While I can certainly agree with this last quote I would simply state that this ‘bad conscience’ exists inside and outside of the Christian heritage.

“You say the world was given a conscience BECAUSE of Christianity but then you say in comment 6 that you do not believe that. So I don’t see how you can accuse me of not reading your post carefully or not understanding it when I stated that you focused on Christianity causing the bad conscience.”

Dexter, one of the problems with your comments is that you seem to be using conscience and bad conscience interchangeably. They are not the same thing. Rico did not write that the world was given a *conscience* because of Christianity. he wrote that James and Friedell recognized something the world had been given as a result of Christianity, that being a *bad conscience*. Your using these terms interchangeably is why it looks like you don’t understand what Rico is writing about.

“#5’s reading is so weak I’m not sure its worth the effort to correct it, or even just mock it.”

This seems a little unneccessary. Since there was clearly no malice in jmb’s comment, I wonder why you feel like it’s not worth it to correct it. If Rico is using terms such as ‘bad conscience’ that are terms of art, then the fact that his readers do not understand the point of his post is his fault, not theirs, because he did not adequately explain himself. Meanwhile, you are willing to criticize people not for their opinions, but simply for not knowing what these terms mean, though you also didn’t provide any additional information. Alternately, perhaps you and Rico just want to have a discussion that is confined to those who are “properly” educated in ethics/theology/history.

I will concede that I am not properly educated in ethics/theology/history.

@Douglas Hunter

I hope you got a laugh out of my naivete.

Nevertheless, I guess I still don’t get why my comment is laughable. To me, the bad conscience is like the internal detector that no matter who is in charge, we ought to consider the way we do things, and stand up for what is right.

My point is simply that this has been taken to the opposite extreme, and in the name of benevolence and virtue towards everyone, we are now in the business of forcing people to be benevolent. Now, we feel vindicated that our leaders, our gov’t, are caring for the poor, the needy, the downtrodden. But alas, we have overlooked the “force” part. In the name of “caring for the needy” we have lost the part of the bad conscience that tells us that forcing people to do things, even to be charitable, is, in itself, immoral. That was at the core of Lucifer’s plan in the pre-existence after all.

In other words, we are “bending with the breeze” and rather than oppressing others as many dictators, and tyrants have done in the past by exercising unrighteous dominion, we use altruism as our motivation, and compel others to care for people. I submit that this is still wrong, and our “bad conscience” ought to inform us of this.

But I may still be completely confused here.

p.s. thanks brjones for the nice defense!

#10- Granted my comment was pretty obnoxious. That being said, my beef with #5 is less the author’s lack of background than the author’s opinion and insertion of / reliance upon a feeble political ideology, and a false argument. Guess that I should have made that more clear.

Be that as it may I would hope that any reader would be able to notice that the OP specifically used the term bad conscience. Is it too much to ask that readers would notice that? I would hope that a reader would say to themselves “interesting, this post uses the term bad conscience, even though I am more used to thinking in terms of just conscience, I wonder why that is?” One need not know much of the specific philosophical or theological history of these terms to notice the difference, but one may need to have that kind of knowledge in order to respond well, or to avoid poor replies on internet blogs.

#12 – I think this is a fair point, and the author’s use of the two different terms is pretty clear. That said, ‘bad conscience’ is not such a distinct term that one would automatically know that it is a term of art. I also think it would have been helpful for the original post to include a brief explanation of what that means, since the post was basically premised on a quote in which that term was a central idea. (not to criticize, Rico) Without further explication, this post is difficult to really understand and discuss for someone with little or no knowledge of the terms being used.

Hmmm, I guess I’m still confused. Re Douglas #12, I certainly did notice the difference, and it did in fact cause me to wonder about it. In fact, I even looked it up, and tried to learn something about it without becoming a scholar. I guess I’m really still confused.

I thought this here was the key:

I thought that’s what I was pointing out.

Douglas maybe you could enlighten me as to why my comment was so silly. I’m being sincere here, I truly want to understand what I’m missing.

Rico, could you jump in and help me see more clearly what you’re trying to say. I fear I may have missed the boat entirely.

When Friedell and (I presume) his biographer James used the term “bad conscience,” they were using it in the context that Nietzsche gave the term:

“Enmity, cruelty, joy in pursuit, in attack, in change, in destruction—all those turned themselves against the possessors of such instincts. That is the origin of “bad conscience.” The man who, because of a lack of external enemies and opposition, was forced into an oppressive narrowness and regularity of custom impatiently tore himself apart, persecuted himself, gnawed away at himself, grew upset, and did himself damage—this animal which scraped itself raw against the bars of its cage, which people want to “tame,” this impoverished creature, consumed with longing for the wild, which had to create out of its own self an adventure, a torture chamber, an uncertain and dangerous wilderness—this fool, this yearning and puzzled prisoner, became the inventor of “bad conscience.” But with him was introduced the greatest and weirdest illness, from which humanity up to the present time has not recovered, the suffering of man from man, from himself, a consequence of the forcible separation from his animal past, a leap and, so to speak, a fall into new situations and living conditions, a declaration of war against the old instincts, on which, up to that point, his power, joy, and ability to inspire fear had been based.”

“Bad conscience,” to the atheist Nietzsche, was a Bad Thing — the suppression of a strong man’s instincts for strength, for no good reason and with self-destructive result.

If Christ be not risen (or absent some equivalent to the promise of the Resurrection), Nietzsche was right. A strong man should feel no compunction about seeking as much dominance as he can get away with.

Douglas i’d like to invite you to follow in the footsteps of Egon Friedell and jump out a window.

#17 – Where did this come from? Is this some kind of inside joke?

#7 – Douglas, I always enjoy your thoughtful responses but fear you have too much respect for my thoughts. I has been a while since have seen a comment of yours here and am pleased that you have returned. I think that your comment explains very well what I clearly failed to express. I agree that I do stand, or try to, outside the dominant position that power leads to truth. I feel that our approach to ethics should be a dialogue with God as we struggle to live ethical lives.

#8 – Although I agree with #9, I do recognise that perhaps I was not clear in my writing. I apologise for this. I believe that from the western point of view that Christianity brought with, the potential for the ‘bad conscience’, but that other traditions may also have done this independently of Christianity (my knowledge of these other traditions is limited and hence I reserve judgment). I say potential because I do recognise that not all Christians developed this, but I do believe that it may have originated, in the western tradition from within the Christian context. I hope this more clearly expresses my view, but I am not suggesting it is infallible. I also agree that it exists out side the Christian tradition, my point in raising this here, is that I sense I have not developed this ‘bad conscience’ as well as I ought.

#10 – I agree that I could have done more to explain. I certainly do not want a discussion that involves only the initiated. Thank you for noting a weakness in my writing, I readily acknowledge that i am not the best writer.

I sense that my basis in the UK means that I could respond adequately. I have to say that #17 is unnecessary.

I am no expert on the ‘bad conscience’ as some others clearly are. I use these forums as a place to work out my own thought as much to benefit from the comments of others. I think this may be why I am sometimes unclear, because I am still working it out myself.

I don’t think you missed the boat, I just think that Douglas disagreed strongly with your position. I too think that you are wrong, but I can understand your position.

Rico – Joseph Smith – “God said, “Thou shalt not kill”; at another time he said “Thou shalt utterly destroy.” This is the principle on which the government of heaven is conducted-by revelation adapted to the circumstances in which the children of the kingdom are placed. Whatever God requires is right, no matter what it is, although we may not see the reason thereof till long after the events transpire.” – Are we encouraged to oppose oppression ?

based on the premiss – if Christianity helped establish the might is not always right (bad conscience), then Mormonism has sought to re-establish that Power (Authority) is right regardless of the cultural attitude at the time.

I would propose that it was the Humanist movement that infiltrated Christianity in the 1400’s that gave rise to the modern “Bad Conscience”.

#20 – Thank you for your response. I find this statement by Joseph Smith very troubling. Not because I do not think it is correct, but more that from a personal perspective I struggle with the implications for my faith. Moreover, I sense that God uses of the ‘thou shalt utterly destroy are so rare and, perhaps necessary, that they would not contravene my moral sensibilities. In fact, it is this circumstance that perhaps provides a real challenge. I mean, the Nazis were defeated by extreme violence. In opposing this might = right attitude it is sometimes necessary to use might; herein is the paradox of this idea. My own feeling is that Mormonism, at least as I conceive it, gives me the scope to develop a dialogue with God over what is ethical. I am not a big fan of absolute ethics. You may well be right about you idea about the ‘bad conscience’. I do not know enough to challenge you. However, I sense that Christianity has gone through phrases of embracing this and rejecting it. I would argue that during the time when Christianity was not linked with any particular state, it probably encouraged the ‘bad conscience’; however it was eroded when it became linked with political structures. Consequently the phrase you speak about may have been another later phrase which exploited an already latent potentiality.

#19 – Rico, I think you are a good writer, and I apologize if I implied otherwise. The fact that you didn’t explain a term does not make you a weak writer by any means. In any event, my response was directed toward DH’s response to others’ responses, and I think I understand where he was coming from, and vice versa.

“Rico – Joseph Smith – “God said, “Thou shalt not kill”; at another time he said “Thou shalt utterly destroy.” This is the principle on which the government of heaven is conducted-by revelation adapted to the circumstances in which the children of the kingdom are placed. Whatever God requires is right, no matter what it is, although we may not see the reason thereof till long after the events transpire.”

And with this we have really come back to Rico’s earlier post on Kierkegaard. I’m glad we have gotten here because its an important place. It raises an issue that I have been unable to think through it in a satisfying manner. At work is the question of does God command that which is good, or is something good because God commands it. Clearly JS felt that something was good because God commands it including violence.

The problem we have today is that if we believe that God can and does suspend the ethical when it suits him, if we believe that violence and destruction can be commanded by God, then we share a stunning structural similarity with those who crash air liners into buildings, or detonate bombs in public places. These horrific acts are done in the name of God by those who believe they are called by either by their religion or directly by God to do these things. Obviously the reply “They do that because they believe in a false god but we believe in the TRUE God” is of no help at all. If anything this structural similarity shows the degree to which faith occupies a space in excess of the rational and the ethical. This is a great potential and a great danger of faith.

brjones – i did not take it personally. Thank you for your kind comment, but i do write my posts a little too hastily, and unfortunately I lack the natural ability to do that.

Douglas – I know we have visited this question before, but it too is one that keeps recurring for me. Perhaps this is why I connected with this idea in the first place. I do not have a good respond to the big questions, but as I said before, I feel that God expects a dialogue on what is ethical for me on a day-to-day level. Perhaps, closer to home, for some of us, is whether God would ever ask us to do something that might lead us away from the Church or back into it.

Genesis 18 – God describing his desire not to destroy Sodom or Gomorrah to Abraham.

I think that this scripture demonstrates the capacity God has to allow dialogue, personally IMO God wants us to take a stand ethically where necessary, we should be anxiously engaged in a good cause and try to do it of our own accord. (D&C 58)

I don’t think there is any scriptural accounts of god commanding anyone to kill anyone else after the Birth of Christ… is there?

oh yeah and #17 was inappropriate… sorry bout that…

#26 – I agree that there is not, that i am aware of. But are you saying that God has changed or that those types of commandments were for a different time or place? I guess I see it as still conceivable, if we believe it happened in the first instance.