This two-part episode features a fascinating, dynamic, and soaring discussion that takes us into the experiences, cultures, and elements of the worldviews of Latter-day Saints from Pacific Island nations. We learn pieces of the history of two of these nations as it relates to the LDS Church taking hold there, what elements resonate with those who are from the “islands of the sea” (D&C 1:1; 2 Nephi 29:11), and the ways that Mormonism integrates into the daily lives of, especially, Maori and Tongan Saints–including places where Polynesian culture does not allow white Mormon practices and ways of seeing to penetrate, such as with the ceremonial use of kava, notions of family and various power dynamics within families, and funeral practices. In letting us into their lives and perspectives, the panelists also take us deep into the experience of forming identities shaped by both Polynesian and white cultures, which also allows us to see very clearly how there truly are no “neutral” spaces–how “whiteness” carries values and perspectives that are often invisible if not explored through the comparative process. In this Mormon Matters episode, we are privileged to have powerful and open yet charitable guides into these (often wonderfully evocative) tensions.

This two-part episode features a fascinating, dynamic, and soaring discussion that takes us into the experiences, cultures, and elements of the worldviews of Latter-day Saints from Pacific Island nations. We learn pieces of the history of two of these nations as it relates to the LDS Church taking hold there, what elements resonate with those who are from the “islands of the sea” (D&C 1:1; 2 Nephi 29:11), and the ways that Mormonism integrates into the daily lives of, especially, Maori and Tongan Saints–including places where Polynesian culture does not allow white Mormon practices and ways of seeing to penetrate, such as with the ceremonial use of kava, notions of family and various power dynamics within families, and funeral practices. In letting us into their lives and perspectives, the panelists also take us deep into the experience of forming identities shaped by both Polynesian and white cultures, which also allows us to see very clearly how there truly are no “neutral” spaces–how “whiteness” carries values and perspectives that are often invisible if not explored through the comparative process. In this Mormon Matters episode, we are privileged to have powerful and open yet charitable guides into these (often wonderfully evocative) tensions.

Some of the specific topics discussed in this episode: Polynesian views of passages in the Book of Mormon that seem to tie darker skin with unrighteousness; the Church-run Polynesian Cultural Center, “performing indigenity,” and both the difficult tensions some experience related to different modesty standards as well as the positive ways that performing culture for entertainment purposes can lead to increased opportunities for people from these island nations; mixed views among Tongan Mormons about the film The Other Side of Heaven; the hyper-sexualization and sometimes infantilizing of Polynesian peoples; how gender roles often play out in much more balanced ways in Maori and Tongan cultures than they do in typical U.S. Mormonism; grieving styles; and some of the consequences for Polynesian youth in Utah and the U.S. of identity diminishment from language loss and separation from one’s family’s roots and cultural history. Then in the podcast’s transcendent final twenty-five minutes, we are privileged to hear firsthand from our panelists telling about their lives and work exactly what it means to claim an identity and embrace the responsibilities that come with that choice.

This episode features panelists Gina Colvin, a Maori Latter-day Saint living and teaching in New Zealand, and Anapesi Ka’ili and Luana Uluave, two Tongans with strong roots in both Tongan families and Utah Mormonism who share a great love for the gospel and each part of their identity but also have wonderful independent perspectives. Mormon Matters friend Joanna Brooks and host Dan Wotherspoon facilitate the discussion, but they are mostly simply thrilled to play a small part in bringing this discusion to listeners. One of the best Mormon Matters episodes of all time–informative, humbling, inspiring!

Please listen and join the conversation in the comments section below!

____

Link to Gina Colvin’s blog, KiwiMormon

Comments 23

Im really surprised that there aren’t any comments yet. Maybe because there is so much goodness in this podcast that it seems almost too much to handle/talk about. All I can say is that this was a fantastic podcast. I have a feeling that I will return to this one often. Great job everyone!

Thanks so much Jacob! I’m taking the ‘quietness’ on the discussion as a sign that we had it all wrapped up!!

Wow! This was an amazing discussion. So much new and good information for me. I really loved it.

Having always lived in backwoods Texas, I didn’t run in to any Pacific Islanders until my mission to the Philippines. There was a Tongan in my batch that trained and traveled from the MTC together out to the mission field.

My second mission companion was actually half Maori. What a wonderful sweet guy. I’ll never forget him. His dad was Maori and his mom was a Caucasian English professor at BYU-Hawaii. He was 6’6″ tall but was so calm and happy. He helped me to chill. I was such an uptight missionary! He told me he didn’t know his dad very well and that his dad had a bad temper. He said his dad had also returned to his

When I was in the mission office as the secretary, we had a Tongan elder that got frustrated with the mission president and reportedly had a gun that he was threatening to use against him. We stayed up all night in the mission office for him to show up. We hired armed guards for the mission office and the mission home. When he finally showed up at the mission office, the APs talked to him calmly and nothing happened.

In my last area where I was zone leader for a long time, there was a new area being opened. A Samoan from New Zealand was the branch president. He was awesome and everybody loved him. He really helped take care of things out there. They even built a simple bamboo shelter for a meeting house. He had a Tongan companion and there was another set of Samoan elders that lived with him. That house was crazy, but they got along really well most of the time. I’m so grateful for the hard work they did. I was too ignorant to know how to deal with them, and I don’t think I ever earned their respect.

One interesting tidbit I heard when I was there is that they won’t send Caucasians to the southern missions in Mindanao because of the Muslim terrorist issues. They send Filipinos, Samoans, Tongans, Maori, and African Americans because the thought is that they won’t be taken hostage by terrorists.

I know the half Maori elder you are talking about and he is about the chillest coolest guy you will ever meet. Small world.

Thank you for this amazing discussion!

I’m a Dutchman married to a Tongan, and I strongly identify with the polynesian culture.

We’re in the process of starting up a Tongan Branch of the Church in Las Vegas, so I was hoping to hear some discussion on that particular topic. I guess others have spoken and written on that topic before, so I was not disappointed not hearing it being mentioned in the discussion, especially because a host of other interesting things were talked about.

One of the things I took away from this discussion was how polynesian culture – where our Church is often quite dominant in society – has the potential to draw a stark contrast with the overall “palangi” culture in the Church. There is a great need for discussion about cultural values in the Church, and the Polynesian culture is one of the few who is able to stand its ground and insist on relevance.

I’m still working on finishing podcast but I’d like to point out something about the discussion of race, Pacific Islanders, and the priesthood at about 1 hour into the first installment. Although it’s true the Polynesian and Pacific Islanders were not denied the priesthood before 1978, the priesthood ban was in effect for Melanesians (indigenous peoples of New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and New Caledonia). It’s a little tricky was the policy was in Fiji and for Australian Aboriginal Peoples, but it is clear that the church treated Melanesia much like Africa (an evangelical no man’s land) before 1978 and there were no Melanesian members given the priesthood until considerably long after the ban was lifted.

Although it’s great that many Polynesian and Micronesian peoples did not have to endure the same kind of racial discrimination as people of African and Melanesian descent, I believe the policy ultimately ended up racializing the theology even more profoundly. Historically, Polynesian missionaries to Melanesia (especially the Methodists, Anglicans from the London Mission Society, and Mormons) have had a very long history of racializing Christian theology around some of the speculations of Anglo or British-Israelism. Mormonism simply provided a space for many Polynesians to incorporate themselves within that same racial narrative and find the “other” in the Melanesian people.

This isn’t a simple story of finding a positive theological space with one’s racial identity. Such positive stances usually come at the cost to the proverbial “other.” In this case it the “other” was found in the Melanesian people of the South Pacific. As a side note, the vast majority of LDS Missionaries to the New Guinea and the Solomon Islands are still from Polynesia. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing but I have begun to wonder how wise it is. I recently had an incredibly disturbing interview with a former Mission President to a part of Melanesia. He was from French Polynesia and was adamant about the racial superiority of the Polynesian people. He discussed at length on the “child-like nature” of the “very dark-skinned” people of Vanuatu. His claim was that while the Polynesian people were descendent from Hagoth the Melanesians were clearly descended from Cain. Ouch! I’ve always been concerned about the infantilization of Pacific Islanders by Utah Mormons but it’s not like that narrative isn’t reproduced in the Pacific as well.

I should note that I pulled out my Bislama (the lingua franca of Vanuatu) and 2 Ne. 30:6 basically still refers to the “scales of darkness” but the end is translated as a “clean and good people” rather than “pure [or white] and delightsome people.” I’m actually quite surprised by this translation because as a creolized language born of the pidgin language encounters between English and French speaking Blackbirders, plantation owners, missionaries, and the indigenous ni-Vanuatu, Bislama can be pretty un-p.c. sometimes. For example, in Bislama “child of God” is “pikinini blong God.” I believe there’s even some moments in the Bislama Book of Mormon where people are warned of being a “fak up [bum].”

In terms of translations into indigenous Melanesia languages, that is likely to never happen. Bislama (Vanuatu), Tok Pisin (Papua New Guinea), and Solomon Islander Pijin are too prevalent in a region of the world with the highest density of indigenous languages.

I guess there’s another comment to add before I finish the podcast. At about 11 mins into the second installment there’s a discussion of traditional Maori sexual practices and genealogy. In fact, Maori kinship is a form of what us anthropologists would call ambilateral affiliation. Traditionally Maori kinship enables a person to claim affiliation with any one kin group through either parent and to different kins of the same order through both parents at once. This allows Maori to trace their descent through multiple links, both maternal and paternal, at one time. The kin unit referred to in the podcast is the whanau, which is not necessarily matrilineal and is but one of the four kin groups.

Thank you for the wisdom to create this podcast Dan and Joanna. Respect to the panelists who were able to speak with relevance about their culture and the ways in which Mormonism worked on behalf of their cultures, and seemingly the way their cultures worked on behalf of expanding the body of Mormon thought. It is a hopeful podcast (for me) in that I have not been misguided in placing hope in the younger generation to help in taking the reins for the future cast of defining and redefining Mormonism, shifting from many of the remnants of 19th century strongholds that have lost place in redefining Mormonism in this century and centuries going forward. It was notable to me the soul beauty of these women in presenting a wider way to think about a more global Mormon culture. And by that I do not mean a homogenized global culture, rather a culture that can embrace the beauty within multiple cultures and bring those elements to bear on present day. I could well learn from them, as can many I’ve encountered among the Mormon culture.

I just finished both installments of the podcast. I really really enjoyed it. I’m very happy that Dan and Joanna let Gina, Anapesi, and Luana shine on their own. The comments about cultural spins on classic “Mormon lessons” was great. I can’t emphasize how true and profound the discussion was about the fault being with the child that didn’t share rather than the child who “stole.” I also loved the discussion about funerals and the power of mourning together as a community.

The part on the the Polynesian Cultural Center was great. I’m not sure if the panelists are aware of it, but there’s a nice little article in An Anthropology of Indirect Communication (2001; Edited by Joy Hendry and C.W. Watson) by Terry Webb on the Center. The article is called “The temple and the theme park: intention and indirection in religious tourist art.” It plays on the theme park tourism and the exoticism of “culture” that is perpetuated by the Center. I was also saddened by the discussion of the exploitation of Polynesian bodies as sexualized objects for display. I think the panelists were right on about that.

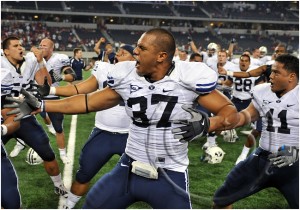

I also really enjoyed the discussion of the haka. We had a very long discussion about this on the listserve for the Association for Social Anthropology in Oceania (ASAO) shortly after those people were maced after performing a haka by Roosevelt. The phenomena of Pacific Islanders performing the haka was become quite globalized (an anthropologist in Paris has done great work on the performance of the haka during rugby games throughout Polynesia). However, it is actually usually something like the Siva Tau (Samoan). Gina was quite right to suggest that it can be rather offensive when non-Maori participants perform it, especially when it’s led by a non-Maori. I believe the haka usually performed by the BYU football team (there are many youtube clips of this) is the Ka Mate version. Gina was right to point out that there are rather problematic politics about the performance of this haka, as it is the recounting of Te Rauparah’s triumph over death and his escape from his enemies. The Ngati Toa (a Maori “iwi” or tribe) tried to keep the Ka Mate from being used in commercial and sports events because they felt the the appropriation of their cultural dances was offensive. They have not succeeded in the effort. Just think about how offensive it is to many Native Americans when we name a sports team “The Braves,” or some other misappropriation or caricature of indigenous culture. I know that some Polynesian saints like the performance of the haka during BYU games, but I believe it needs to stop. It’s really quite offensive to many Maori. The Maori scholars I know on ASAO were livid about BYU performing it (particularly when in, at least one youtube clip, it was led by some white Mormon). There’s even a youtube clip of the white BYU football players performing the haka with nothing but towels on. There’s also lots of youtube clips of white missionaries performing it (I saw one performed in the MTC without a single Maori present) and I’ve also seen it performed in Boy Scout PowWows (also offensive on multiple levels) without a single Maori or Pacific Islander present. It’s pretty ridiculous.

The closing statements of Gina hit so close to home it was scary. I decided along time ago that I couldn’t hide my Mormon identity from my colleagues and that I should openly discuss my critique of Mormonism with them. My experience has been very similar to Gina’s. I think they’ve grown to appreciate Mormonism more and realize that my faith and identity was far more complex than the image of Mormons that was readily available to them. I remember during one conference someone made a snide remark about me being an “imperialist” because of my Mormon roots. Almost immediately several people jumped to my defense (not that I needed it) and quickly responded that they didn’t know anyone who was more committed to radical politics (I’m an anarchist) and who was more willing to critique the things they hold dear than I am. I’m pleased that Mormon Matter’s featured these great panelists to facilitate a thoughtful discussion on the role of culture, identity, and faith. This was truly a special podcast with great women, scholars, and saints. Thanks for all involved!

Love your comments Jordan! Thanks so much for all of your feedback and thoughts. You’ve made some really interesting points which obviously comes out of your training as an anthropologist! Wonderful!!!

I would agree with you on the Haka but would be careful to use race as a marker for who can and cannot appropriately perform the Haka. My son is half maori/half haole but looks very white and I would hate for race to disqualify him from ever participating authentically in his cultural heritage and roots.

The ‘All Blacks’ certainly do complicate the performance.

Wonderful podcasts! I grew up with many Islander friends, but we never got into in-depth discussions about the interplay of their ethnic and religious heritages.

It also made me want to repent for performing the haka probably a dozen times or so as a teenager. I played rugby for a high school team in SLC which always had a strong contingent of Maori and Tongan players and the coach of which was enamored with Polynesian culture, though he was Anglo. We performed the haka (ka mate) a few times a year, always led by a Maori, and I – and many of my Anglo teammates – never really had any second thoughts about it. Truth be told, many of the Kiwi and Tongan teammates didn’t seem to either (or at least they didn’t express them).

However, towards the end of my high school rugby career though, our team went on an international tour, in which we faced a New Zealand side. We prepared to do the haka, but our Maori teammate who normally led the haka refused, and walked away looking both embarrassed and angry. The absurdity of performing the haka to a primarily Maori side dawned on me, and I began to realize how colonial and offensive our appropriation of Maori cultural elements was.

I loved hearing about how the panelists viewed the racial parts of the Book of Mormon and how different it was from Anglo members’ views. No wonder so many Islanders go to Tongan (and other nationality/ethnically-based) wards in the Salt Lake Valley.

Thanks again for this!

That was an incredible podcast. Thank you!

I would love to see more podcasts that get into different subcultures within the Church culture. It’s so important for us to keep hearing that the way it’s done in Utah doesn’t mean it is the only right way.

I will definitely have a different attitude about the PCC if I ever go back to Hawaii. Does anyone have suggestions regarding how I can honor and learn about the island cultures without exploiting them? I have this on my mind because we are headed to Thailand this fall and I have been looking into ways to experience the Golden Triangle without taking part in some of the harmful practices that go on there. I want to be a tourist that helps not harms.

Here, here! A series or some such on the experiences of different people of color in the church would be amazing!

Re: hakas and such performed by BYU athletics. (I know nothing about the BYU football

The BYU rugby team has their own original haka, created by the Polynesian players at the Polynesian players’ request, IIRC.

It looks like there are different opinions by on the appropriateness of the tradition being done and with whom it is done and why it should be done. As many stakeholders in the culture are offended as are not, it seems.

I’d have to agree that Wayne and the boys did a good job with their new haka and as long as Wayne and Ray etc. are there I don’t have a problem with it in its current manifestation. But what happens if and when they leave, who is going to look after it, the reo and the tikanga? What worries me is the wholesale appropriation and plunder of this particular tradition by football teams across the US. Unfortunately in the US it has turned in to a spectacle without due respect for the tikanga, with little care over the reo and with hardly any recognition as to the importance of haka as a lyrical composition by iwi for iwi. And furthermore who is there in the US to look after it, to answer questions about tikanga, to have a living conversation about its boundaries and exclusions, and the proper conduct when doing a haka, and being on the receiving end of a haka? I just can’t help feel a bit possessive of it as something by NZ Maori, for NZ Maori on NZ soil or if not something that represents NZ elsewhere not a spectacle for Americans, given by Americans, received by Americans and watched by Americans. Wayne did the right thing in having a korero with the folks back home but who else is doing that? Certainly it would appear, not the BYU football team. Bronco needs a smack on the bum for bastardizing something that has a turangawaewae which isn’t the Wastach front notwithstanding the couple of Maori he has in his team.

Loved this podcast and it comes at a great time because I find myself living in a predominantly polynesian ward in a foreign country in the midst of a faith crisis. With these two occurring at the same time, I have really struggled to feel a sense of belonging and have wondered how both of these come into play.

The podcast was beautiful and I absolutely loved the part about the funeral differences.

As a side note, I’m a bit tired of the Utah mormon references. I know, I know, there is some truth to the generalization, but I know that most of you are careful not to make these generalizations about other groups of people. I’ve spent enough time outside of Utah to know that many of the cultural assumptions, practices, etc are thriving (and sometimes worse!) in wards that have very few “Utah mormons”.

I came upon this podcast by accident and I just want to thank Don and Joanna for facilitating a discussion on the topic of Pacific Islanders and the LDS Church and the fine panel of scholars who were each able to provide unique insights, analyses and criticisms. I am an active LDS Samoan who grew up in Hawaii, attended BYU-Provo and now lives in Samoa, so I’ve spent a lot of time examining my culture and religion and the areas where they intersect. I’ve only been able to listen to the first half of the podcast so far, but there are just a few of things that I wanted to add to what panelists said. I agree with Dr. Colvin’s criticisms of the PCC, but I think she missed a very important point.

PCC not only dumbs down south pacific cultures by short-cutting them into 30 minute block presentations and a Las Vegas style cabaret show, it perpetuates the myth that pacific peoples and cultures are a monolith. Similar to Dr. Colvin’s experience in working at the PCC, I have a cousin who is full Samoan who works at PCC and has taught the poi dancing in the Maori village, danced to the drums in the Tongan village and danced in the Tahitian village despite the fact that she has no ancestral connection to any of those places. I remember seeing her doing a Tongan dance right next to an Asian looking girl on the deck of a canoe during one of PCC’s daily pagents a few years back and thinking “How can they share a culture and a heritage that is not theirs?” If you take something that is not yours, and you share it with or sell it to someone else, that does nothing to mitigate the fact that you stole it. But at its core, that’s PCC’s business model. No matter how well intentioned such acts are and how many BYUH students get scholarships, theft is theft. The drum beats that are used, the dance movements that are performed, the patterns painted on their costumes and the legends that are told do not travel on the wind or come from the ether. They come from a culture that belongs, collectively, to a people. So far as I know PCC and BYU Living Legends (or Lamanite Generation or whatever they’re calling themselves now) have no license nor any other kind of formal permission to exploit these cultural symbols and practices for gain.

But that is just the insult that is added to the injury that PCC has continually committed for decades by disrepecting the distinctness and uniqueness of Samoan, Tongan, Hawaiian, Maori, Tahitian, and Fijian culture and trying to melt them down into a single, simple “polynesian” narrative in their nightly shows (the latest one called “Ha, the Breath of Life,” is better described as “Ha! An Unfunny Joke and Insult to Pacific People.”) “Polynesia” is concept created by geographers and used by linguists and anthropologists. Ask a Native Samoan what he knows about “polynesian culture” and he will laugh at you and say “nothing.” It would probably be like asking someone from Utah what they know about North American culture. Ask the same Samoan what he can tell you about Samoan culture (or the same Utahn about Utah culture) and he’ll probably have quite a bit to say. Samoans, Tongans, Fijians, Maoris, Tahitians and Hawaiians should all be afforded respect and not packaged and presented as indistinghable for the sake of convenience and profit.

Talofa Tuiatua! I soooo agree with you. Well said!

While on the topic of Pacific Island Mormon Identities, I’d like to let folks know about a new web site my wife and I – together with our son – created: http://tonganwards.weebly.com/index.html

Tongan Wards is an independent collection of studies and video’s as they relate to Tongan LDS faith communities. We’re just getting started with this site, and we hope to get reactions and suggestions.

I enjoyed this podcast when it came out last year. I just came across an article in an old Improvement Era that reminded me of the discussion, specifically about how Mormon pacific islanders identify with the Book of Mormon. I wonder how much this specific article influenced those views:

http://archive.org/stream/improvementera1806unse#page/534/mode/2up