Once again, the story of Symonds Ryder has been misused to illustrate a point about leaving the Church over something inconsequential. Undoubtedly there have been Latter-day Saints who have apostatized from the Church over a small slight. However, the two tales which are often cited when warning of this danger, the Thomas B. Marsh strippings of milk story and the Symonds Ryder misspelled name story, are likely inappropriate in this context.

Once again, the story of Symonds Ryder has been misused to illustrate a point about leaving the Church over something inconsequential. Undoubtedly there have been Latter-day Saints who have apostatized from the Church over a small slight. However, the two tales which are often cited when warning of this danger, the Thomas B. Marsh strippings of milk story and the Symonds Ryder misspelled name story, are likely inappropriate in this context.

In a post at BCC, John Hamer gave a thorough history of Marsh’s disaffection with the Church and concluded:

“Thus, while the moral the Thomas B. Marsh fable, i.e., that faith can be shattered over something inconsequential, is true enough, it would probably make sense to tell a different, more appropriate fable to illustrate that moral.”

The same conclusion can be reached by considering additional aspects of Ryder’s story. A talk in the Sunday morning session of General Conference by Donald L. Hallstrom titled Turn to the Lord referenced the Symonds Ryder story as follows:

Symonds Ryder was a Campbellite leader who heard about the Church and had a meeting with Joseph Smith. Moved by this experience, he joined the Church in June 1831. Immediately thereafter, he was ordained an elder and called to serve a mission. However, in his call letter from the First Presidency and on his official commission to preach, his name was misspelled—by one letter. His last name showed as R-i-d-e-r, not the correct R-y-d-e-r. This caused him to question his call and those from whom it came. He chose not to go on the mission and fell away, which soon led to hatred and intense opposition toward Joseph and the Church.

In such retellings of the Ryder fable, the misspelling of his name is often the only reason cited as the cause of his decision to then leave the church. (see B. H. Roberts in HC 1:260–61; Fawn M. Brodie in No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith the Mormon Prophet, 118; Donna Hill in Joseph Smith: The First Mormon, 143; Cannon and Cook in Far West Record, 286; Dean C. Jessee in Papers of Joseph Smith, Volume 1: Autobiographical and Historical Writings, 511.) Probably the origin of this story is his funeral sermon preached in Hiram, Ohio, August 3, 1870, by B.A. Hinsdale.

“Ryder was informed, that by special revelation he had been appointed and commissioned an elder of the Mormon church. His commission came, and he found his name misspelled. Was the Holy Spirit so fallible as to fail even in orthography? Beginning with this challenge, his strong, incisive mind and honest heart were brought to the task of re-examining the ground on which he stood. His friend Booth had been passing through a similar experience, on his pilgrimage to Missouri, and, when they met about the 1st of September, 1831, the first question which sprang from the lips of each was–“How is your faith?” and the first look into each other’s faces, gave answer that the spell of enchantment was broken, and the delusion was ended. They turned from the dreams they had followed for a few months, and found more than ever before, that the religion of the New Testament was “the shadow of a great rock in a weary land.” (A. S. Hayden, Early History of the Disciples (1875), p. 251.)

Perhaps the misspelling was a bother to Ryder, but this one incident was hardly the sole reason for Ryder’s departure. For one thing, spelling was more fluid in the 19th century and earlier. An attempt at standardized spelling in the U.S. did not begin until the appearance of Webster’s “American Dictionary of the English Language” in 1828, and for at least a half century many words continued to be vociferously debated. American census-takers varied quite a bit in their reporting of people’s names, showing that they were not asking people “How is that spelled?” but rather writing the name as they thought it should appear. Ryder’s name appears as following in the U.S. census:

1830 census Hiram, Portage, OH: Simonds Rider

1840 census Hiram, Portage, OH: Symonds Rider

1850 census Hiram, Portage, OH: Simonds Rider, wife Mahitabel

1860 census Hiram, Portage, OH: Symonds Rider, wife Mehitable

1870 census Hiram, Portage, OH: Symands Rider, wife Mahitable

Ryder’s commission with the misspelling of his name took place in June 1831 and may account for his not going to Missouri, but as noted he did not leave the church until Ezra Booth’s return in September. In the meantime, Ryder became concerned about other developments. In a letter to A.S. Hayden he wrote:

“But when they [Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon] went to Missouri to lay the foundation of the splendid city of Zion, and also of the temple, they left their papers behind. This gave their new converts an opportunity to become acquainted with the internal arrangement of their church, which revealed to them the horrid fact that a plot was laid to take their property from them and place it under the control of Joseph Smith the prophet. This was too much for the Hiramites, and they left the Mormonites faster than they had ever joined them, and by fall the Mormon church in Hiram was a very lean concern.” (Symonds Ryder, “Letter to A. S. Hayden,” February 1, 1868, cited in Hayden, op. cit., pp. 220, 221.)

It seems that the coming threat of enforced consecration might have been more of a problem for Ryder than the misspelling of his name. The influence of his disaffected friend Ezra Booth must have also had an effect upon Symonds.

The Religion 341 Church History manual states:

“From the outset the Church had an unpopular public image that was added to by apostates and nurtured by the circulation of negative stories and articles in the press. People gave many reasons for apostatizing. For example, Norman Brown left the Church because his horse died on the trip to Zion. Joseph Wakefield withdrew after he saw Joseph Smith playing with children upon coming down from his translating room. Symonds Ryder lost faith in Joseph’s inspiration when Ryder’s name was misspelled in his commission to preach. Others left the Church because they experienced economic difficulties.”

Such a view boils the disaffection of these individuals down to a single, easily dismissed anecdote rather than acknowledging the difficult and complex issues they faced. This practice encourages members today to dismiss the very real concerns confronted by members who question aspects of the Church. “If you have questions, you must be sinning,” the party line goes. In reality, there are multiple tangled and tortuous reasons why someone may develop a crisis of faith. Not only should we look deeper into the available documents to discover the motivations of historical figures, we should listen, and listen, and listen some more to come to a greater understanding of our friends and associates who question.

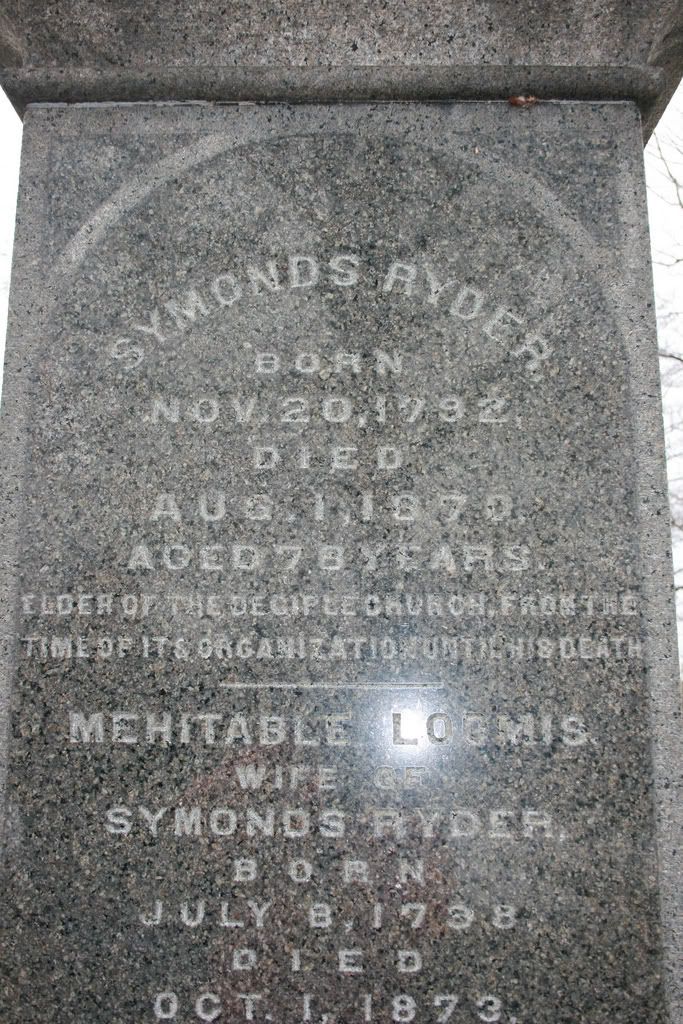

As for Symonds, poor thing. If he was really so concerned about spelling, he must have rolled over in his grave when they placed this tombstone — with the name of the “Desciples” church spelled wrong!

Comments 38

That gravestone is truly cosmic karma

I should note that Thomas Marsh’s story was reinforced by a number of things he said on his return to the Church. As a result, it has become, in a way, the very example of what it attempts to criticize. That is, someone takes a story, simplifies it, and then uses it for a point it does not stand for. In Thomas’ case, the irony strikes me.

As to Rider/Ryder of the Desciples, I rather think that the story rather catches that people often have a trigger point or a tipping point that looks very inconsequential when looking back. I’ve listened to a number of stories that had that sort of thing as an element. Sure, there are many other narratives, but the sad thing is that there is also that one that happens to be true, much like the variety of ways that people have affairs. Is any one path the only way to mess up a relationship? Of course not. But does that mean that any particular narrative is false? It doesn’t.

Once again we see that the church historians are more concerned about “faith promoting” stories rather than the truth, which is what we’re supposedly seeking. I have news for them: People don’t like having things hidden from them, even in the Lord’s restored church. A good friend of mine has had his faith shaken because of things like the Missouri-Mormon wars, the Mountain Meadows Massacre, and even the accusation of Joseph Smith having an affair with Eliza R. Snow. We’re told that none of us are perfect and we all sin, but why is church history always presented to us in a way that makes the early saints appear perfect and infallible, especially the ones who didn’t fall away for a time? Fortunately that isn’t the approach the Lord takes in the Doctrine and Covenants. It is full of rebukes and chastisements prior to comforting messages to help lift the saints back up afterwards.

You “but” is very very telling in your sentence. “We’re told that none of us are perfect and we all sin, but why…” We expect Church Historians and General Authorities to produce all the details of all the accounts before any of the evidence is uncovered. We did not receive the documents and full accounts of either episodes until recently (I work for the CHL). I don’t expect anyone to be perfect but I don’t like it when antagonists point a finger at those they expect to be perfect.

I think this is key. Having experienced this myself, I could look back and say that the Prop 8 ordeal was inconsequential. Indeed, it was the “trigger,” but hardly the reason. Things were building up, dissonance abounded, and it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. However, any characterization of me that included Prop 8 as the “reason” I had a faith crisis would be sorely misleading, unfair, and offensive!

BiV, I really appreciate the history lesson. It’s only through debunking the myths that we keep the history real and pure and avoid letting it become nothing more than a simplified moral lesson. I like to understand people, not just glean over-simplified moral lessons from their lives.

“If you have questions you must be sinning” as the party line? What party is that?

And #3 David P — on church historians: a rather broad brush, don’t you think? (The same one you claim they use, perhaps?) I don’t know whose history you’re reading these days, but certainly recently produced histories of Joseph Smith and Mountain Meadows don’t fit that mold.

I thought the same thing as I listened to the talk. I think the problem is that the Church leaders have to keep things on an over-simplistic, milk level so as not to upset the apple cart.

Why? I think the root of the problem is that they are nervous. When I was younger, the message was very controlled. The only way to find out much about the “non-official” version of our history was through “anti-Mormon” books and literature. You had to specifically seek much of this out.

With the rise of the internet, much of this information is now very easily available – the majority of which actually uses fairly official sources. Conversion rates are dropping as a percentage of membership, and more members seem to be having issues. The natural reaction to this is to “circle the wagons” and “rally the troops”. We hear talks about things being “faith-promoting” as opposed to being historically correct. If you are a GA, you will take this to heart as you are writing your talks or articles or what-have-you. Ironically, I think a more open strategy would work much better. I think the current strategy just sets people up for a bigger fall when they inevitably find out more information. Any one of those facts could then be the “trigger”.

Honestly, I think simplified story telling is so common because it is all that endures. But the truth is ALWAYS more complex. We need to remember that before we swallow some of these stories (as well as things in the scripture). There are always multiple viewpoints, forgotten details, etc. BiV – great post! I really enjoy these types of debunkings. We should have enough charity to recognize slander. I once heard someone defend Satan in Sunday School, for crying out loud! Surely we can have enough charity to encompass Ryder and Marsh.

The other issue is that the WW2 generation (silent generation) prefer black & white thinking with heroes and villains. That’s just not as appealing to subsequent generations who want nuance, complexity, and acknowledgement of the gray in life. This is the difference between the Brady Bunch and Modern Family or between Marcus Welby and ER or between Leave it to Beaver and Lost.

@Paul,

I wouldn’t say it’s too broad of a brush. The Church has, to be certain, been far more open and forthcoming regarding historical documents and events in the past decade. However, it needs to be noted that those sources and subsequent books are there for people to find. As a member of the Church you are free to pick up and read the Mountain Meadows book, the Joseph Smith Papers, or Rough Stone Rolling, and might even be encouraged to do so on rare occasion by a fellow member. However, few in the Church are going to actually make that effort. I know plenty who have purchased some of these new resources but have simply placed them on their shelves to read “someday”, and plenty of others who simply couldn’t care less. The only history that most members learn is the history taught to them in Church itself and, while the manuals have been written in such a way that they technically don’t mention many of the old historical myths, they do nothing to resolve those myths that are still being passed around and will probably come up in the class discussion; there’s also plenty of oversimplified and bad history still contained in them. Plus we still get these stories told in General Conference and subsequently published in the Ensign: I’d look pretty horrible to say that a story shared by a general authority is either far to simplistic, without needed context, or is simply unsupported by the available documentary evidence. A synthesis of the newer historical openness with Church curriculum and sermons would definitely go a long way to helping everyone have a better understanding of things.

I had one other off-the-wall observation. There seems to be a weird trend in the church, especially among GD teachers, to prize the history volumes, the older they are – even when they are full of easily debunked falsehoods. I don’t know why this is, but I’ve seen teachers pull out some dusty old tome with pride, and been able to debunk what they said before they even finished reading the passage with a quick lds.org or google search. Dates & facts, all mixed up, nevermind details and conclusions!

@6: Mike S — I can’t speak for why church leaders do what they do. I do recall a talk from Elder Packer years ago in a PH Ldrship session of a regional conference in which he talked about the complexity of teaching a global (and fairly young) church, so I suspect that colors some of the thinking.

@8: NCN Tom — (Cool enough, BTW) I think we’re not far apart here. But I see hope that things are improving. It’s not to say that access to records might tighten up again, but with all the alternative sources available, that horse seems to be out of the barn. As for leaving those books on the shelf to read “someday” — that was the place the Book of Mormon held when my family joined the church in the late 60’s — it seemed relatively few members had read the whole thing. So maybe we’ll keep growing up. I hope so.

@#7 — HG — thanks for your statement of a thought rolling around in my head. Simplified storytelling is what endures, and truth is more complex. I have to chew on the simplification of the WW2 generation, though…

Fwiw, I’ve said in meetings that stories mentioned in GC are too simplistic (both general meetings and leadership meetings) – and nobody has argued with me. Now, that’s largely because I say it softly and non-argumentatively and short conext highlights – and also because everyone knows I’m a dedicated member and not saying it to start an argument or “bash” anyone.

Over-simplifications are published all the time everywhere – inside and outside religion. It’s the nature of trying to use real-life examples to teach a particular point and not having enough time to do so fully. I don’t like when it happens in the Church, and especially in GC, but I take the kernal of truth that is in each story (the “tipping point” aspect, usually) and understand it’s an overly-simplistic generalization. It’s going to happen long past my death, so I accept it as what it is.

Just as an example, everything said about this story could be said with equal accuracy about most of Jesus’ parables. Most of them paint with a very broad brush and don’t deal with nuances at all. To avoid that, it takes writing the story of Job or Jonah or Daniel in its entirety – and that ain’t going to happen in GC.

Oh, and great post, BiV!

Excellent post BiV. You have presented history as it should be taught. Thank you very much. There really is no excuse for bad history.

BiV, the minute I heard Elder Hallstrom tell that story, I immediately thought of milk-strippings and figured somebody in the bloggernacle would address it, and it’s not a surprise that it was you. Glad you did.

There really is no such thing as a simple story in real life, but it is also hard to make a clear point with a nuanced story. Not that that’s an excuse.

I wonder how much of the Bible is just like that: oversimplified stories from one, two, or four generations back, used to illustrate simple morality lessons.

It could be that the Book of Mormon is full of that, too.

I work at a bookstore in SLC and we had Mark Staker here last night to talk about his new book “Hearken O Ye People” (from Kofford) which gives incredibly detailed historical context for the Ohio revelations. Among other things, he deals with the Symonds Ryder episode and concludes that the misspelling bunk is just that, bunk. In a chapter dealing with Ryder and Ezra Booth, Staker points the finger at Ryder’s being uncomfortable with “the law” in general and consecration specifically.

Great post, BiV.

Steven and jmb re: “tipping points” — exactly. It’s like saying that World War I happened because some Austrian royal who nobody really liked much got himself shot. The backstory matters.

#5 re: “broad brush” — Even Richard Bushman, the latchet of whose historiographical shoe I am not worthy to unloose, still falls into the trap of polishing things up. For example, he quotes a letter by a former Mormon making it seem as if Joseph was trying to dissuade the Missouri Danites from issuing death threats to Oliver Cowdery and other then-disaffected members, telling them (paraphrasing), “I don’t want anyone to do anything illegal.” The full quote, though, is (again paraphrasing) “I don’t want anyone to do anything illegal, but just so you know, the Bible story about Judas hanging himself isn’t true. He was hanged by Peter.” Changes the meaning from an unalloyed “calm down, guys” to “you guys have something of the right idea about how to treat traitors.”

#4 Ray — Oversimplification is inevitable. The problem is that when you have to use an oversimplification to make a point, perhaps the point isn’t worthy of being made, or at least supported by you only partly-true anecdote.

The bottom line is that the Church, as its wagons are presently circled against challenges to its foundations, simply has to blacken the character of doubters. For every faithful skeptic with his proverbial shelf stacked with neatly-wrapped doubts with plenty of room for more, there are at least some people who would apostasize at first contact with these things — and so the only way to keep them is to dissuade them from questioning at all, like those silly petty people Ryder and Marsh. And doubtless this approach works in enough cases that it’s deemed worthwhile.

Not sure I like it, but I tell myself it’s none of my business. Determining how the Church presents its narrative and keeps apostasy tamped down is above my pay grade.

“This caused him to question his call and those from whom it came. He chose not to go on the mission and fell away, which soon led to hatred and intense opposition toward Joseph and the Church.”

I’m thinking of these sentences individually and their reliability.

“This caused him to question his call and those from whom it came.” Questionably true based upon a funeral sermon given 40 years later.

“He chose not to go on the mission” True

“and fell away” hmmm….

“which soon led to hatred and intense opposition toward Joseph and the Church.” Based upon his letter written 37 years later, it appears “opposition” was correct. Can we really rely on the evidence from church history that someone heard a voice saying “Simonds, get a bucket a tar.”? Isn’t it possible that there may have been another Simonds in the area? Amidst the commotion and in the darkness, was it possible to know from enunciation only that the name called out was Simonds? Is it documented who actually said that they heard the name called out?

#17: “Can we really rely on the evidence from church history that someone heard a voice saying “Simonds, get a bucket a tar.”? Isn’t it possible that there may have been another Simonds in the area? Amidst the commotion and in the darkness, was it possible to know from enunciation only that the name called out was Simonds? Is it documented who actually said that they heard the name called out?”

And let me add, “Given the tendency in Church culture of hostility towards dissenters, is it possible that in the account referencing ‘Simonds’ and the tar bucket, which appears to have been written long after the fact, is somebody’s faith-promoting invention — like the stories of how all the murderers of Joseph Smith all supposedly died horrible deaths?”

Maybe I’m just too suspicious of everything. Heck, I wonder if something fishier went on with Ananias and Sapphira than the stingy old pair just happening to drop down dead in front of Peter. Imagine if today’s anti-Mormons had been anti-Christian Jews or Romans when that episode happened.

I guess I find this kind of stuff a bit nit-picky in some respects. For folks who become disaffected from the church, it is typically a series of things that actually make that happen but there may be a single triggering event to start it and a “straw that broke the camel’s back” to complete it. So, while it might be a stretch to pin Symonds disaffection on the misspelling incident, it may have had some play in it and it might have started the ball rolling. And anyone who has done any family history work knows that names get misspelled all the time, even with the person standing there. So I don’t consider the census any evidence of fluidity of spelling. Even though I acknowledge that that was probably the case at that time. Most could barely write let alone spell.

And what makes the misspelling account any less reliable than his letter to A. S. Hayden. People often cast themselves in a better light when re-telling a story.

And I am not sure what is so faith-promoting about this story and the Marsh story anyway? I don’t consider it that. It might be used as a warning, but then again, most of us have known people who have left for a seemingly small reason. So, it is possible that a lesson can be learned even if the simplest version of the sorry is told.

And finally, if we forced the complete truth from every story ever told, not many could hold up to that kind of scrutiny.

Great stuff, BIV.

I truly hate it when our history is mythologized. It is a human mistake, but we should resist it. Thanks for the reminder.

BiV, fantastic post. I remember hearing this talk and wondering if there was more to the story.

I’ll have to double-check some files to get the exact details, but Rider/Ryder spelled his name differently himself! There was clearly something else going on. And Staker’s new book is indeed a great place to find some of those details.

Amen to this!

Re Jeff

The thing is Jeff, you’ve nailed it on the head. Left for a seemingly small reason. Sure the misspelling had something to do with it, but that’s the point, it wasn’t the entire reason as was indicated in the story. The story was a mischaracterization at best, and a half-truth at worst. Honestly, while I think we can understand what leads to such stories, I really don’t think it’s wise to excuse it.

The census can’t be used as evidence of how someone spelled his name. The census was taken in those years by an enumerator, who went around to the households and wrote down the name of the persons living there. It could be that the enumerator was an old friend of the Ryder family, and surely he wouldn’t need to ask Mr. Ryder how to spell his name, would he? And even if he did ask, he may have recorded it wrong.

And putting Elder Hallstrom into the World War II generation is simply a mistake (but not worse than the over-generalization that that generation somehow tend to cast things in black/white terms.) The only living general authorities who actually fought in World War II are Pres. Packer and Elder Perry. Pres. Monson joined the navy in the summer of 1945, and the war was over by the time he shipped out. Elder Hallstrom was born in 1949.

we were talking about this in Institute about two weeks ago. I had never herd of the story before. so, I took at face value what every one was saying.. The point, that I’m trying to make is this. That when someone tells you something about church folklore, history and what is in the standard works and you don’t know for sure if its’ true, its’ our responsibility to read, and investigate the veracity of the statements. This doesn’t make one a bad member

“Symonds disaffection on the misspelling incident, it may have had some play in it and it might have started the ball rolling”

In Seifeldian terms the story could be retold as:

“His name was misspelled by one letter. This caused him to question his call. Yada, yada, yada, he left the church and came to oppose it.”

Only in the talk, the yada, yada, yada was omitted, and THAT was the best part.

Mark B., I am using the census information to show that nineteenth-century spelling was still fluid. This is well attested in other places. For example, in the second edition of Webster’s dictionary published in 1841, he continued to note the variants of two spellings which were equally common (such as music and musick), and to recommend spellings which were not generally in use but made more sense orthographically (as when he wrote under the entry for ‘mold:’ “the prevalent spelling is ‘mould,’ but as the ‘u’ has been omitted in the other words of this class, as bold, gold, old, cold, etc., it seems desirable to complete the analogy by dropping it in this word.”)

We tend to think of our names as having one correct spelling, but in Ryder’s day, that was not the case. To the dismay of genealogists, there were people at this time who signed their OWN NAMES using different spellings at different times in their lives.

Rigel and others, I am not so sure that the misspelling of Ryder’s name had ANYTHING to do with his apostasy.

#26 Rigel: Any General Authority who actually said “yadda yadda yadda” in Conference would instantly rocket into my top ten favorites list.

Re #27

I agree, the information in the post makes the connection between spelling error and apostasy dubious.

From your study, do all the accounts of the spelling error story seem to be drawn from the funeral sermon, or was there apparently an oral tradition that filtered into the various accounts?

Also, any idea of the month(s) when Joseph and Sidney went to Missouri, as described in his 1878 letter. Did that take place before the tarring and feathering of JS?

On the other hand, looking at the signatures of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, it is easy to see that some men took great pride in the spelling of their name, and would be miffed to see it misspelled in a commission. When I’ve done church records, even computer program glitches that result in name issues seem to rankle some people.

Thank you BiV. This was a great post with thoughtful comments. I never knew the background on the Ryder story.

The mispelling of his name planted the seeds of doubt in his heart. All members have questions, but when those questions begin to turn to doubt that is a different story entirely. I think that’s the point the “mispelling” of his name story is trying to illustrate.

“’If you have questions, you must be sinning,’ the party line goes.”

What party line? Where does it say that in LDS teaching or sources?

It’s OK to have questions. Symonds should have talked to Joseph Smith about the misspelling and cleared things up between himself and Joseph.

Personal apostasy from the church can be complex and my experience is that people will not tell the real reason at first. Symonds Ryder may not have properly understood and accepted the Law of Consecration, but when asked why he left the Church said because they spelled his name wrong. It may have been, and I can only conjecture, that he did not publicly state the real reason till later in life. I learnt, early in life as a missionary, that when someone gives a simple cause for their inactivity then it is likely a false reason. I need to enquire more and hopefully they will share what the real reason is. Nonetheless, I really do appreciate your deeper research into this mormon myth.

Just a quick comment: the flexibility of spelling in early America also affected the brother of the Prophet, whose very Masonic name is variously spelled both Hiram and Hyrum, depending upon the document you are reading. 🙂

When we see in the news a brother shooting and killing his brother over who gets the remote control for the TV, is it too hard to imagine people leaving the church over little things? Also, quoting a letter a disgruntled apostatized member wrote 30 years after he left the church? People make mountains out of molehills and we all know how stories can take a life of their own, especially when someone has strong feelings about it – makes you wonder how much of anything Simonds said 30 years later would be very close to the truth. And – why does this author not give a name? Curious!?

Pingback: Settle this in your mind, and move forward! | The Millennial Star

Can you please share the reference where you paraphrased that Peter hung Judas? I find that fascinating. Thanks!!